Welcome to the applications laboratory. Here is where we play, consider, experiment and assemble. In this method, Chen Taijiquan applications are not stored in eroding antique books or museums, or the rarified hands of ordained “masters”, but in the hands of those who build the body method and movement patterns by long term bitter form practice.

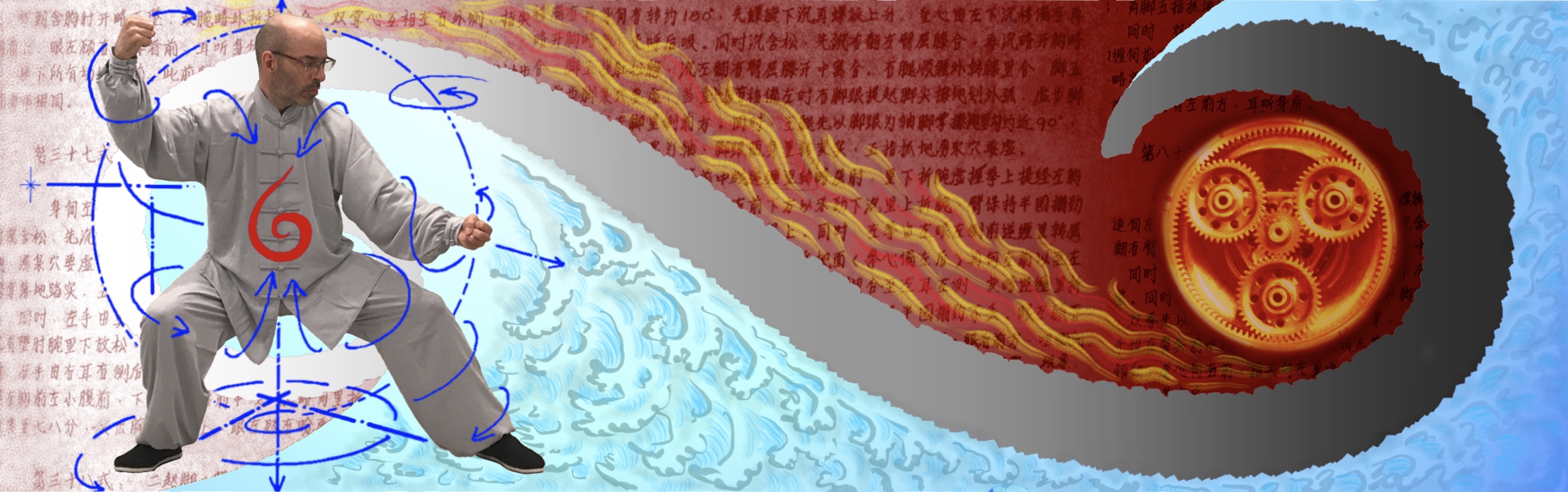

In this video we explore a number of possibilities for application derived from sections of a move/sequence from Yilu Quan called “Tuibu Yazhou” or, retreating step press elbow. Specifically here we focus on ways to use very small sections of the form, such as a single foot method on its own or a two handed change that many people would simply pass over as a transitional movement.

This style, commonly referred to as a form and labeled “Xinjia” or New Frame Chen Style Taijiquan, in popular (mainstream) exposure often does not bother with these tiny sections of the forms because most often when this “form” is taught along with others the depth of detail in these tiny sections is either not learned or taught, or not seen as important.

In the family line of this style, every inch of the form practice is considered important. There are in fact no ‘transitional’ sections of the form that are devoid of their own useful jin or method. Even though sections may be artfully strung together using apparently connecting movements, these movements in themselves are also training specific jin.

*************

This is how we do it some days, but when not on camera everyone gets to try it and drill it. This is not supposed to represent any absolute ideal response or situation in actual conflict. It is to explore possible options one can use if they seem suitable in a particular moment, in particular positions and relating to specific energies or method that one might be faced with. Besides whether or not these particular method might be suitable to anyone’s situation, they are simply useful ways to begin to think about what and why one might be practicing certain Jin and sequences for in form training.

In this type of study it is important to let go of preconceived notions of how things should look and the idea of looking good at all, and just look at function. In a live situation there is no one there to comment on whether or not you are leaning or you look like you are demonstrating Taiji. If you understand the origin of the Jin your are using and have developed it in the body from proper gongfu practice and it WORKS, that is enough.

A surefire topic for controversy as discussed here, is also the idea of Peng, the wheel and the dent. Many styles of Taijiquan do not have what is commonly called “Chuan Zhang” or piercing palm. This may be why many do not consider the need to deal with it and hold the belief that Peng is the answer to just about anything. Peng of course is a great answer, until it is not.

In many dynamic situations we might choose (as we did not here) to simply use footwork and surrender space when faced with a crushing force. It is most often a better idea to be safe and avoid taking on a struggle in a tight spot such as extricating one’s self from Chuan Zhang and just step out or around, but it is of paramount importance to learn how to continue to flow from the territory and root that one occupies before choosing to step out, or step at all.

This is a specific difference between for example, Bagua Zhang and this type of Taijiquan. Expanding from the concepts of tuishou, Taijiquan works from root and established position first, then once control and change is ‘mastered’ within the limits of position, change of position is involved. This is not due to a lack of interest or curriculum in footwork, but more an desire to train stability and proficiency in any position one may find themselves rather than being forced to change position by an opponent. Positional change should be elective rather than compelled.

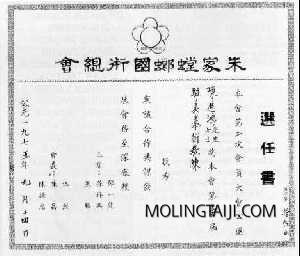

Chen had achieved ‘master’ status in Southern Praying Mantis—also known as Zhu Gar, or Zhu family gongfu—during his youth in Hong Kong. Zhu Gar is a Hakka (southern) system that is in fact not related to other mantis systems at all. According to Chen, the Zhu family changed the public name of their system in the interest of self-preservation, after facing persecution by the incoming dynasty of the day due to their family connections to the previous dynasty.

Chen had achieved ‘master’ status in Southern Praying Mantis—also known as Zhu Gar, or Zhu family gongfu—during his youth in Hong Kong. Zhu Gar is a Hakka (southern) system that is in fact not related to other mantis systems at all. According to Chen, the Zhu family changed the public name of their system in the interest of self-preservation, after facing persecution by the incoming dynasty of the day due to their family connections to the previous dynasty.