Late Autumn 2014 Marin Spivack, Chen Shi Taijiquan Gongfu Jia Er Lu “Pao Chui”

Late Autumn 2014, Marin Spivack Chen Shi Taijiquan Gongfu Jia Yilu Section

This is Gongfu Jia. Chen Shi Taijiquan detailed, focused practice to produce a lasting practical result or ’embodied gongfu’ ability. Many distinct features of Chen Zhaokui’s method are evident in this practice passed down the family line from Chenyu.

Chenyu Chen Shi Taijiquan Gongfu Jia, Zhuozhou, Hebei School

I recently made a visit to Chenyu’s new Chen Taijiquan school location in Zhuo Zhou, Hebei, about an hour and a half south west of Beijing (without traffic and road construction). Originally Chenyu had basement level school location in a building adjacent to his residence in Liu Jia Yao in Beijing, and then it was moved to an upper level in a different location, but space is at a premium in Beijing and the available space in Hebei is huge and ideal.

Zhuozhou can be reached by train from Beijing west train station, and there is also bus service, if I remember correctly, #838 from Beijing, but one needs to research those details on site. In my case we traveled by car.

Zhuozhou can be reached by train from Beijing west train station, and there is also bus service, if I remember correctly, #838 from Beijing, but one needs to research those details on site. In my case we traveled by car.

At the time we made the trip one of the major highways on the route was undergoing repairs, (more…)

Chen Shi Taijiquan Bailagar (Long pole) Marin Spivack, Chenyu Dizi

Bailagar Long Pole, Chen Taijiquan.

There are many practice forms, these are a few, deceptively simple, simply difficult. The heavier the pole, the worse it looks.

Contrary to how it may appear to those who are not familiar, this wood is really NOT so flexible as it appears. This thickness of Bailagar “white waxwood” will not carry a wave unless the practitioner can forcefully send and control it.

Chen Taijiquan Boston Tuishou Class Excerpts 2014 陈氏太极拳推手

Chen Taijiquan patterned tuishou, in this case Dalun, is a most useful training method for clear development of JIN. These days this facet of traditional Chen Taijiquan training is sorely neglected and often just seen as a cursory circle to begin a competitive wrestling bout. In fact this practice is where many of the gems of structure and technique are found. Here are some views on very basic training.

Traditional Chen Taijiquan “Kulian” bitter basics training

This (at least visually) illustrates some of the unique methods of the Chen Zhaokui line of Chen Taijiquan as relates to basic structure. This is “jibengong” basic traditional instruction for those who are physically willing and able. It is not for everyone, but the path of “zhen” (true) gongfu in this style. Here is a rare look at some non-commercial traditional training.

Two slightly different feelings of Chen Taijiquan Yilu as the seasons changed

Tuishou & Qinna

Fun stuff:

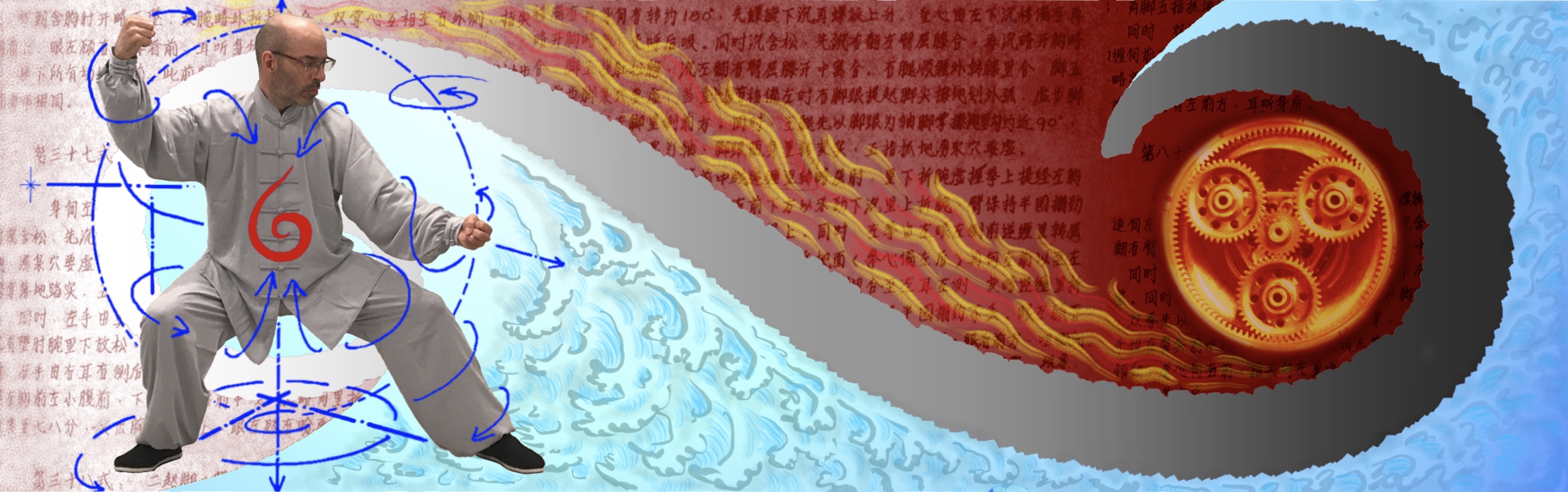

Chen Family Taijiquan Unpacked: Gongfu Utility System

[Above: Chen Taijiquan Gongfu Utilities, Bow & Arrow Fist]

Chen Taijiquan Gongfu Utilities is a teaching and practice curriculum that I have developed over many years of personal practice, research and teaching. After many years of consideration I have decided that at least some of it needs to be shown and even publicly taught if the opportunity arises before Taijiquan’s last traditional coffin nail is hammered.

Chen Taijiquan traditionally is what I would call a “packaged system” as if packed into a suitcase for travel. The main elements of practice in current popular Chen Taujiquan are (more…)

Chen Shi Taijiquan 5 moves on Ice & Snow; How to pull a groin in 5 easy moves..

When practicing on a very slick surface the integrity of the stance is under attack as there is nothing on the ground to hold onto. In this situation the only thing keeping the shape of the stance and the upright position is the action of what we call “Dangjin” or arch/crotch power. “Crotch Power” is certainly an attractive term on it’s own, but in this case it is very laborious.

The legs must not only hold one upright properly, but also must hold themselves from slipping outward. In this practice with a lot of effort the stance can be maintained, until Fajin as you can see at the end, just shakes that rear leg loose. Losing three inches can lead to losing three feet very quickly and a badly pulled groin muscle.